The Ministry of Mitzi Budde

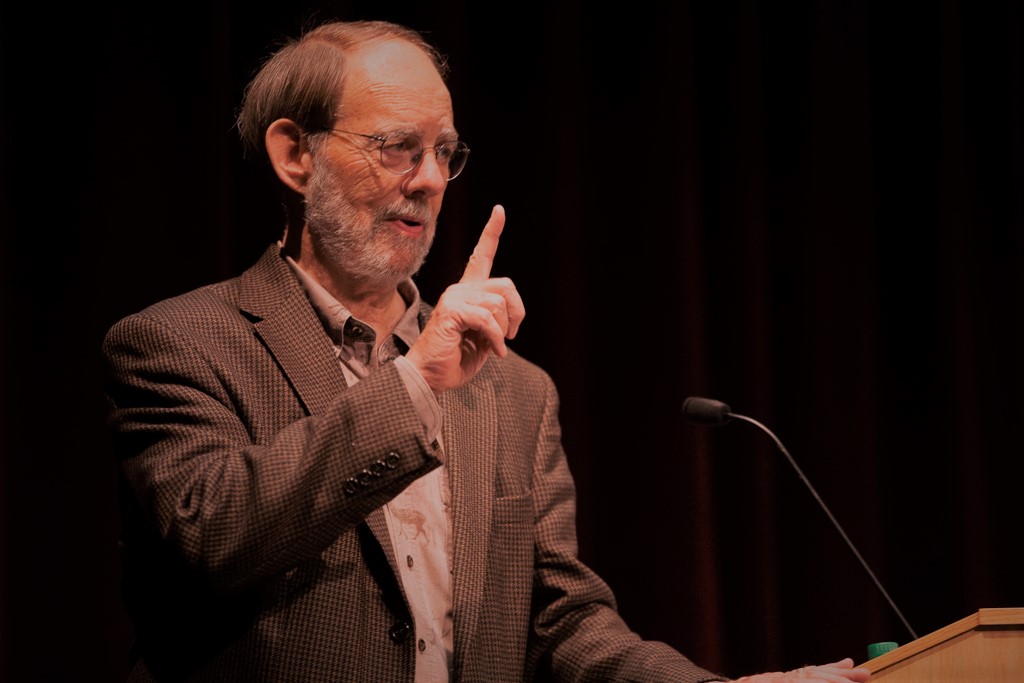

Mitzi Budde, D.Min, Head Librarian and the Arthur Carl Lichtenberger Chair for Theological Research, retires after 33 years. The Rev. A. Katherine Grieb, Ph.D., ’83, reflects on the profound impact she has had on VTS.

Together we make The Episcopal Church stronger

Senator Reverend Raphael Warnock explains why he considers democracy to be spiritual work and voting a form of prayer.

Senator Reverend Raphael Warnock, Ph.D., made history on January 5th, 2021, when he won a runoff election to become the first African American to represent Georgia in the Senate. He was also the first Black Democrat to be elected to the Senate by a former State of the Confederacy. Warnock was elected alongside Jon Ossoff, who also made history by becoming the first Jewish senator from Georgia and the first Jewish senator to be elected by the Deep South since 1878.

“Georgia voters did an amazing thing. In a contentious and historic runoff election, they elected their first African American senator and their first Jewish senator in one fell swoop, a state in the old Confederacy elected me and John Ossoff… I think somewhere in glory, Martin Luther King Jr. and Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel were giving each other the high fives,” he said.

But his celebration at being elected was short-lived, as his victory on January 5th, was followed by the storming of the U.S. Capitol building on January 6th, which he described as “the other side of the complicated American family story.”

“The good news is that it is not our whole story. It is not all that we are. We are also January 5th, where a kid who grew up in public housing, one of 12 children in my family – clearly, they read the Bible: ‘Be fruitful and multiply.’ – the first college graduate, can now be sitting in the United States Senate. We are both January 5th and January 6th, and now we come to this point where, once again, the latest generation of Americans gets to decide which America we are going to be.”

Delivering a lecture titled “God’s Politics Now” at Virginia Theological Seminary, Warnock said this tension was not just two opposing political visions, but rather two countervailing views of the Christian faith itself. As a result, he said for him, faith and politics went hand in hand.

“It is for me spiritual work. It is moral work. It is the work that we are called to do in this moment, because democracy is not just a political undertaking, I submit that democracy is the political enactment of a spiritual idea,” he said.

Warnock, who has been Senior Pastor of Atlanta’s Ebenezer Baptist Church, the spiritual home of the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., since 2005, explained that if we are all children of God and have a spark of the Divine within us, we ought to have a voice. “The way to have a voice is to have a vote in the direction of the country and your destiny within it. I believe that a vote is a kind of prayer for the world,” he said.

He added that as America stood between two opposing political visions and countervailing views of the Christian faith, people must choose carefully which path to take. “We need prophetic leaders and the leavening influence of a prophetic community if we are to redeem the soul of America.”

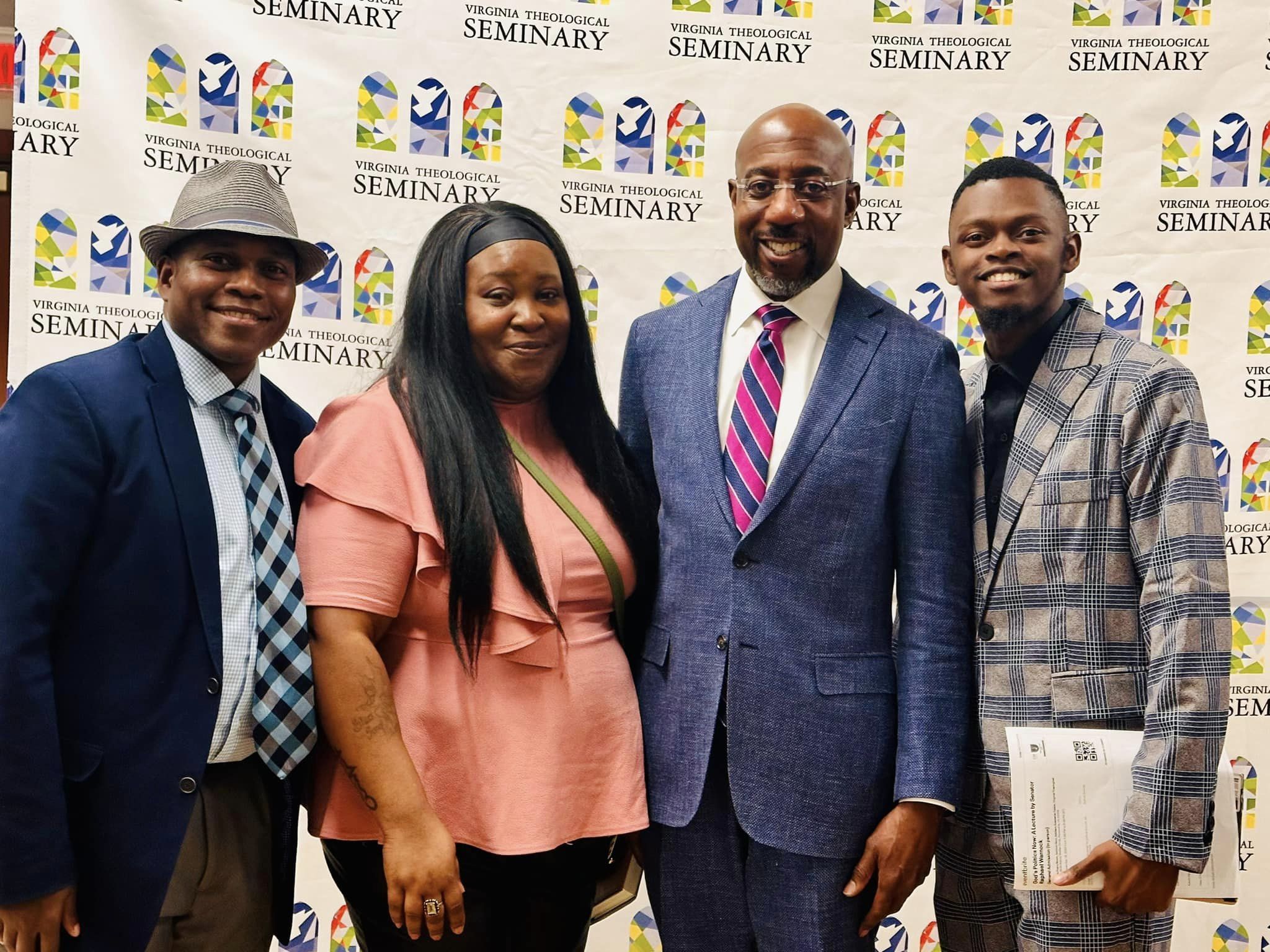

Guests pose with Senator Reverend Raphael Warnock after his lecture.

Warnock pointed out that the Black church was born fighting for freedom, and this focus should also be the raison d’être of any Christian church. He added that, in many ways, ensuring that those two sides of the faith, the pietistic and the political, the social and the spiritual, were not truncated, had been the task of the Black church tradition among the American churches.

“The Gospel means freedom, human freedom, the Gospel means liberation. And while the Black church itself does not always live up to that ideal, there is, as Gayraud Wilmore and others have pointed out, a kind of cohesive thread that runs throughout the history of the Black church that emphasizes liberation, born out of experience.”

Warnock added: “They gave us scraps and we made soul food. They gave us the blues and we made music. They gave us the Bible and pointed to Ephesians and said, ‘Slaves obey your masters.’ We took that Bible and said, ‘What about Exodus? Where God told Moses to tell Pharaoh to let my people go.’”

He said Martin Luther King, Jr., was part of this liberation tradition, and it was these traditions of faith that informed his own work as a politician. “All I’m trying to do in my own way is to give voice to the values of my faith. I’m not in love with politics. I’m in love with change. I put up with politics in order to do the work.”

Even so, he believes the Church often falls short of this ideal. “What is it about the faith that allows the Church so often to be on the wrong side, to be the meanest voice in the room? Maybe there’s something about the faith itself that demands a deeper interrogation.”

Warnock recounted a visit he had made to Washington D.C. in 2017, when he and other clergy had called for Medicaid to be expanded. “They were taking money away from the children’s healthcare program while giving a tax cut to the richest of the richest of the rich. I came with other clergy, and said to the legislators who were there, while standing in the rotunda of the Capitol building, that a budget is not just a fiscal document, it’s a moral document. Show me a nation’s budget and I will show you its values. And if this budget were an EKG, it would suggest that America has a heart problem.”

He added that shortly after he had made his speech, he was put in handcuffs and arrested. “But what they didn’t understand is I didn’t mind because I had already been arrested. My mind and my moral imagination had been arrested by this idea that we are better than this, that we could be closer to our ideals.”

Warnock has continued to work towards these ideals, returning to the pulpit every Sunday morning to preach. “I don’t want to spend all of my time talking to politicians. I’m afraid I might accidentally become one,” he joked.

“There’s this running train between the Capitol and the Church, and between both of those places and the streets. I just feel incredibly grateful that I now get to turn my protests into public policy. My agitation into legislation.”

Looking ahead, he pointed out that people should not be surprised about what he described as the current “crisis,” pointing out that power does not concede anything without a struggle.

“I think it is a reflection of this emerging diverse electorate that can send somebody like me to the United States Senate. If you think people aren’t gonna rise up, and that ain’t gonna make some people nervous, I think you’re naive. So, I think people are seeing the ways in which the country is changing, and that makes some people nervous,” he said.

Warnock explained that the best thing the Church could do for the world and for itself was not to be so obsessed with institutional matters, but rather to give itself over to something larger than itself.

“That’s what it means to follow Jesus and that’s what the Civil Rights Movement was all about. It was about taking the faith into the streets and helping it become alive. It’s about the incarnation, the word made flesh and living among us. So, I try to remain focused on the work, both on people’s spiritual formation, because I still believe in that, but in the context of real human struggle and being honest about that.”

Warnock finished his lecture by talking about Civil Rights activist John Lewis. “I asked myself the night before I officiated the funeral of John Lewis, who was my parishioner, what was he thinking when he crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge, knowing that on the other side of that bridge was brute force, police officers with billy clubs. He had on a trench coat and a backpack. That’s it. What was he thinking when he was crossing that bridge? Was he thinking that one day at the end of his life, the whole country would pause to view his funeral and three American presidents from both sides of the aisle would be there? No, he wasn’t thinking that. Was he thinking that he’d be the recipient one day of the Presidential Medal of Freedom? I don’t think he could have imagined that.”

Instead, Warnock suggested Lewis was simply trying to stay alive that day so he could fight the next, because change is slow. “It comes in starts and fits, but by some stroke of grace, mingled with human resilience, he crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge. And while crossing that bridge, he built a bridge to the future and helped to move us a little bit closer to the beloved community. And now it’s our turn.”

You can watch Senator Warnock’s lecture here.

Mitzi Budde, D.Min, Head Librarian and the Arthur Carl Lichtenberger Chair for Theological Research, retires after 33 years. The Rev. A. Katherine Grieb, Ph.D., ’83, reflects on the profound impact she has had on VTS.

The Thomas Dix Bowers Preaching Fellowship Fund was established at Virginia Theological Seminary on May 6, 2008, by family and friends of the Rev. Dr. Thomas Dix Bowers, VTS ’56.

The Rev, Rode Molla, Ph.D., Assistant Professor, and the first Berryman Family Chair for Children’s Spirituality and Nurture at Virginia Theological Seminary, reflects on the legacy of the Rev. Jerome Berryman, D.Min.

Virginia Theological Seminary was honored to confer the Dean’s Cross for Servant Leadership on Ellen Wofford Hawkins in recognition of her deep faith and ability to bring sunshine into the lives of others.