The Ministry of Mitzi Budde

Mitzi Budde, D.Min, Head Librarian and the Arthur Carl Lichtenberger Chair for Theological Research, retires after 33 years. The Rev. A. Katherine Grieb, Ph.D., ’83, reflects on the profound impact she has had on VTS.

Together we make The Episcopal Church stronger

By the Rev. Jonathan Musser ’17

Rector of St. Anne’s Episcopal Church in Damascus, MD, and the chair of the Membership and Promotions Committee on the board of the Historical Society of the Episcopal Church

“The one hundredth anniversary of the founding of the Virginia Theological Seminary in Alexandria was celebrated on Wednesday and Thursday, June 6th and 7th, 1923… Currents of feeling, deep and full, met and mingled, and the Seminary is stronger today because of the memories which came and the hopes and new determinations which were born, as her sons met and worshipped together in the joyful fellowship of the Centennial Celebration.”[1]

So begins the Rev. Dr. W.A.R. Goodwin’s account of Virginia Theological Seminary’s (VTS) centenary service 100 years ago. The word “sons” is emphasized because inasmuch as Dr. Goodwin’s gaze affixed upon the exclusively male faculty and alumni of VTS in that era, untold numbers of women, children, and other men – many people of color and some enslaved – had already contributed, even in those years, to the character and identity of the institution. Contributions which remain largely unacknowledged, even to this day.

In promotion of the VTS Bicentennial play Dust, VTS Dean and President the Very Rev. Ian Markham, Ph.D., observed that: “Telling the story of the past is one of the hardest things for American institutions to do. Because how do you tell the story of the past that’s full, where everything is acknowledged?” Dr. Goodwin’s reflection is but one example of this truth. Historically, white male voices have been central in histories of The Episcopal Church, and the authors of such histories have themselves been overwhelmingly white and male. This is equally true for most histories of VTS. In a limited 3,000-word article, it would be easy to simply regurgitate the tropes, assumptions, and omissions of the past, but this would do no more than feed into a long history of obfuscating and ignoring an incalculable number of significant figures and voices, which have very often fallen outside the purview of what white men think important or noteworthy. In truth, the published record has expanded in the past two decades, especially with the publication of the Rev. Joseph Constant’s 2009 No Turning Back: The Black presence at Virginia Theological Seminary, and the Rev. Judith Maxwell McDaniel’s 2011 Grace in Motion: The intersection of women’s ordination and Virginia Theological Seminary, but there remains much work to do, and my prayer is that in this third century of existence, we who love VTS, warts and all, will be able to tell the story of its past, in the words of Dean Markham, in the fullest way possible.

The Rev. James May, D.D. All photos courtesy of Virginia Theological Seminary Archives, Bishop Payne Library

Advert from the Alexandria Gazette

Former slave quarters.

When I was first approached about this project, I was asked to do a historical retrospective, encapsulating the history of the Seminary, to be paired alongside Dean Markham’s future-focused companion article in this same issue. I proposed instead to reflect upon the ways in which the story of VTS has been told over the past 200 years and to note, when possible, what omissions exist and where further attention in the future might be warranted. The full history of VTS is one of diversity from the beginning, and while great strides are being made to tell that history more robustly, we are still only scratching the surface of the complex story that defines this institution.

The officially-styled Protestant Episcopal Theological Seminary in Virginia finds its genesis in the years following the American Revolution, a time in which the number of formerly Church of England clergymen serving in the new United States decreased by almost 50%.[2] This dearth of clergy was acutely felt in the mid-Atlantic states, and in 1783 a convention of Protestant Episcopal (a name developed in 1780 by churches in Maryland and adopted elsewhere) parishes in Virginia, “passed a resolution looking to the raising of a fund for the education of two young men from their early years for the ministry of the Church.”[3] By 1818, leaders of the now nationally organized Episcopal Church in the states of Maryland and Virginia, and in the new District of Columbia, came together to form The Society for the Education of Pious Young Men for the Ministry of the Protestant Episcopal Church, with the hope of creating a fund and structure to train men for the ministry. Dr. Goodwin refers to this development as “the real beginning of the Theological Seminary in Virginia.”[4] Here too begins our journey into the gaps of the historical record. Seventeen men are named in the founding constitution of the Society (including familiar names like the Rev. William H. Wilmer, D.D., the Rev. John Johns, D.D., and Francis Scott Key, among others), and yet women appear completely absent from the proceedings. This absence is interesting because a growing body of evidence suggests that as far back as the colonial period, women were often the majority attendees at services of the Church, and women of social status frequently took an active role in promoting both education and evangelism. It would be a little surprising then, for such an effort to be the exclusive domain of churchmen, but what, if any, role churchwomen played remains unclear.

The next five years would prove critical to the realization of a theological school in Virginia. At the outset, the Society supported the re-establishment of the chair of theology at the College of William and Mary, and in 1820, the Rev. Reuel Keith, D.D., rector of Christ Church, Georgetown, renounced his rectorship and moved south to take up the post. Soon, however, the Society realized that the college was not a good fit for their goal, and they began making plans to establish a separate institution entirely. The initial aim sought to keep the school in Williamsburg, however, as Dr. Goodwin notes, this effort too failed, owing to a “prevalence of skepticism and infidelity in that locality.”[5] In the three years Keith sojourned in Williamsburg, he had only one student present himself for the course of study in divinity. Between 1821 and 1822, the Convention of the Diocese of Virginia furthered the efforts of the Society by officially establishing funding and a constitution for a theological seminary located in Alexandria. The official founding is dated to the fall of 1823, when Wilmer began instructing an initial class of 14 men at St. Paul’s, Alexandria, where he served as rector. Keith returned north and commenced teaching duties alongside Wilmer on October 15, 1823. Wilmer and Keith thus became the first two faculty of the now formally established Virginia Seminary. Wilmer served VTS until 1826, when he accepted the presidency of the College of William and Mary, a position he held until his untimely death at 45 in 1827. Keith taught at the Seminary until his death in 1842.

In the years 1827 to 1828, the Seminary community, having outgrown the confines of city life in Alexandria proper, began to look west, where land was more abundant. In the words of Dr. Goodwin:

“Into the virgin forests and into the wild ways of the wilderness of Fairfax County came the Theological Seminary in Virginia in the days of its infancy… The Master had long ago said to his disciples, ‘Come ye yourselves apart into a solitary place’… And now, once again, those appointed by Him to teach chose the wilderness and the solitary place as the situation for their Seminary.”[6]

A sketch of General Hospital Headquarters (Aspinwall Hall), Army of the Potomac, by Alfred Waud, circa 1863.

Here too, the histories of Goodwin and others have another gap in the historical record. Across the histories written about VTS, the facts surrounding the procurement of land on which the Seminary sits today are well-rehearsed, but the names are exclusively European and the descriptive language notably austere. Nothing is said of the robust pre-European history of the Seminary’s land, and to this day no significant attention has been paid to this question, at least by those within the VTS community. The very language of wilderness also functions to obscure the reality that there were generations of indigenous people on this land before the Seminary arrived.

In the years following the Seminary’s relocation, the institution outwardly flourished. VTS came to be known as the standard-bearer for the Evangelical Party within The Episcopal Church, and new buildings were erected for students drawn from all over the country. In the years preceding the Civil War, the Seminary regularly graduated classes numbering in the teens to low twenties. Once more, however, the histories have little to say about the complexities which existed in this era. It is noted that several buildings were likely constructed using slave laborers, passing reference is made to the fact that some faculty families owned slaves, and more (but not enough) is said about the strong abolitionist fervor held by many of the northern students. Hardly a word is spoken about those who themselves were enslaved, and as late as the 2010s, the received tradition continued to maintain that the institution itself never owned slaves. The work of the VTS Reparations Program in the past five years has called this assertion into question, and this project importantly looks to put names and histories to the long unacknowledged workforce, which quite literally built the Seminary.

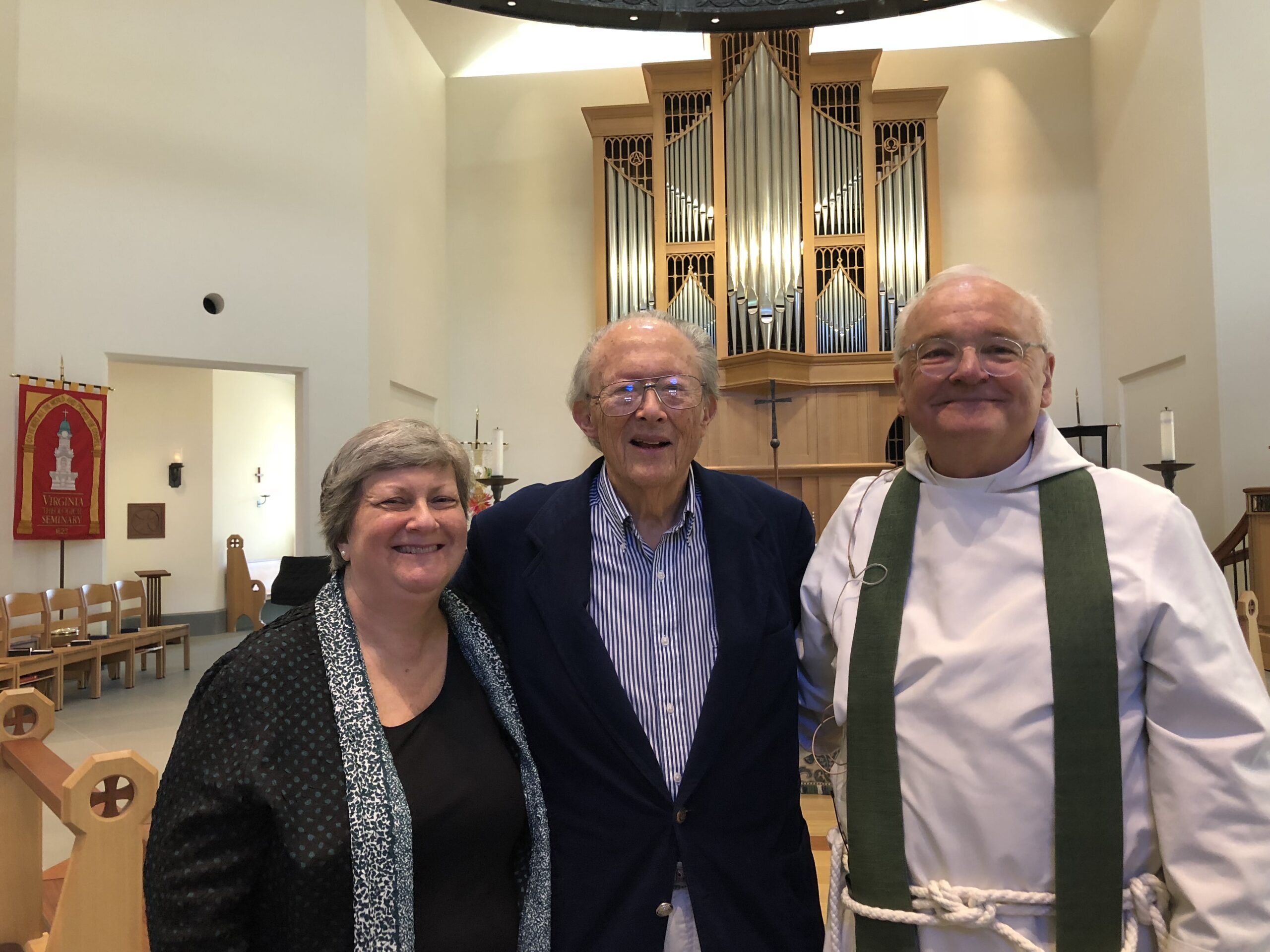

The stories of the women on campus are another major gap. In 1831, Mrs. Ann Wilmer, who had returned to northern Virginia upon the death of her husband, established a private school for children, located in a home next to the Seminary. This effort laid the groundwork for what would eventually become Episcopal High School, but much of her story remains untold.[7] Mrs. Francis Sparrow, was known for her personality and strength of character, but only recently has her story been more fully told as well. My own research, alongside former VTS archivist Christopher Pote, established in 2018 that she had been the petitioner and founding postmaster of the longstanding post office on campus, among a variety of other duties to which she committed herself. Finally, Mrs. Ellen May, the wife of faculty member and abolitionist the Rev. James May, D.D., played an important role in making their home (present-day Maywood) the first ethnically integrated space on campus. In the early 1850s, VTS graduate and future bishop the Rev. John Payne began sending indigenous Liberian men to the Seminary for training. The three students – Musu, Ku Siah, and Siah – were not permitted to reside with the other students on campus, yet the Mays offered their home and hosted all three students during their studies. Much has been made of Dr. May’s role, but there is still much to learn about Mrs. May and her equally important contribution to this prophetic and sustained act of hospitality.

VTS graduating Class 1923.

VTS graduating Class 1873.

The Civil War and Reconstruction eras were quite difficult on the Seminary community. While more than half of the student body came from the north before the war, such representation would not be achieved again until the 20th century. After the war, this left a group of faculty and students emotionally and economically ravaged by loss. Again, we find the historical record lacking and fraught. The truth is that several faculty, and by far the majority of southern students, supported the confederate cause, and the histories too readily focus on their struggles and not enough on the immorality of their misplaced allegiances. Even more problematically, after Alexandria quickly came under control of Union forces near the outset of the war, the remaining seminary faculty and student body relocated south, behind Confederate lines, and continued, ostensibly, as a community in exile. The histories prove scant on the details of this era, and the lack of detail suggests an unease and discomfort with these truths. Both Goodwin and the Rev. John Booty, Ph.D., who wrote the 1995 Mission and Ministry: A History of Virginia Theological Seminary, acknowledge the exile years yet quickly shift to discuss the challenges the Seminary faced in the aftermath of the war. There is much left unsaid about the implications this reality had on the history and legacy of the Seminary, and nothing at all is said about the enslaved community and what became of them in the post-war era.

The next major arc in the history of VTS involved theological shifts and the continued engagement of Seminary graduates in mission work. While in the words of Booty, the post-war years saw a shift from a “…Calvinist Evangelicalism [to] the beginning of an Arminian Evangelicalism with a kinder view ‘of human nature’ and a ‘more generous recognition of the will’s power…’”[8] the Seminary nevertheless remained outwardly a bastion of Evangelicalism within the larger Episcopal Church. This narrative too is complicated by the historical record. A 1903 article in The Living Church claimed that 70 percent of the student body at VTS unsuccessfully petitioned the faculty for weekly celebration of Holy Communion; and, while many students denounced the article, in a letter to the magazine, faculty acknowledged their rejection of the request. Booty notes:

“The Virginia Low Church tradition with its emphasis on simplicity was behind this letter, as was the anti-Roman Catholic, anti-Anglo Catholic tradition of the board and faculty. Some students were always pushing against the tradition: some requested permission to wear surplices when conducting services; one student was required to resign from the Confraternity of the Blessed Sacrament; and another was admonished for making the sign of the cross in the chapel.”[9]

Oakwood in the early 1900s.

What Booty fails to note is that this admission undercuts the picture of VTS as homogenously Evangelical, becoming again an area of study too little dealt with in the history of the institution. This is also especially noteworthy for the Black Episcopal experience, which largely operated in Virginia as an Anglo-Catholic counternarrative to the predominately white “Virginia Low Church” identity. This is an especially important point in the history of Bishop Payne Divinity School, whose full history remains largely untold.

Regarding the Seminary’s long participation in mission work, there is far more to say than can be said within this article. Generations of VTS graduates have played leading roles in national and international mission work, especially the graduates in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The histories, problematically, have largely spoken of this work in uncritical, and at times hagiographical, terms. While the imperative: “Go Ye into All the World and Preach the Gospel,” continues to be foundational to the mission of the institution today, there remains much to reflect on and unpack in relation to the Seminary’s role in supporting problematic forms of mission and ministry – issues which postcolonial missional theology helps to unpack more robustly.

In the 20th and 21st centuries, the historical record improves significantly. Booty devotes significant portions of two chapters to discussing the challenges of racial integration and the admission of women to VTS[10], and these subjects are taken up much more fully and robustly in the two aforementioned works by McDaniel and Constant, in addition to Julia Randle and the Rev. Robert Prichard’s 2012 Hail! Holy Hill: A pictorial history of Virginia Theological Seminary. In the decade since these works were published, however, additional research has uncovered a yet more complex picture of the whole. While much is made in these works of VTS’s transition towards integration, the reality is that lingering issues remain unresolved. Former archivist Pote discovered in 2017 that the post office, so long ago founded by Francis Sparrow, was moved to the edge of campus in 1923 because the Board of Trustees determined: “It will be a great advantage to have the Post Office out of St. George’s Hall, as it is not pleasant to have the porch and hall of that building crowded so much with the negroes of the neighborhood.”[11] Earlier this year, a group of VTS students, staff, and faculty contributed a chapter in Building Dialogue: Stories, scripture, and liturgy in international peace building, which further details the ongoing history of racial tensions within the community and also acknowledges the more recent issue of human sexuality. On that latter subject, very little is presently written and recorded about the history of LGBTQAI+ members of VTS and the incredible challenges they have confronted and overcome across the years. The published histories exclusively focus on the actions of the board and administration, and they do not include the stories and experiences of LGBTQAI+ community members themselves. This too remains a significant gap in the historical record.

Ending where this article began, The Rev. George Bartlett, Dean of the Philadelphia Divinity School, in his address at the June 1923 centennial celebration of VTS’ founding observed:

“The hundred years are past; and still your work goes on. Your eye is not dim, nor your natural force abated. For to you a hundred years is no term of life, after which cometh the end. Rather is it a harvesting time of rich experience and inspiring tradition, which shall give you ampler store of treasure for future sons [sic] and their training in the deep thing of God. And as we greet you proudly on the completion of these fruitful years, we pray and confidently expect that yet greater service shall lie before you in God’s mysterious future.”[12]

Today, it is my prayer that we can say 200 years are past; and still our work goes on… yet greater service shall lie before us in God’s mysterious future. For those of us deeply formed by VTS, there is a call upon us as we mark this Historic Bicentenary. It is a call to look forward to God’s future work ahead, but it is also a call to look backward, with ever greater clarity, on our past and to recognize the brokenness and sin which infects the very roots of the institution which we celebrate. As Dean Markham admonished, let us look forward and backward, and commit ourselves anew to a difficult and challenging truth telling in which our past is most fully and completely acknowledged.

Invoice to VTS for the errection of slave quarters, 1860.

[1] William Archer Rutherfoord Goodwin. History of the Theological Seminary in Virginia and Its Historical Background, Vol. II (New York: E.S. Gorham, 1924), 541.

[2] Robert W. Prichard. A History of the Episcopal Church: Third Revised Edition (Harrisburg PA: Morehouse Pub., 2014), 150.

[3] Goodwin, History, Vol I, 122.

[4] Goodwin, History, Vol I, 122.

[5] Goodwin, History, Vol I, 545.

[6] Goodwin, History, Vol I, 157.

[7] Goodwin, History, Vol II, 411.

[8] John E. Booty. Mission and Ministry: A History of the Virginia Theological Seminary. (Harrisburg PA: Morehouse Pub., 1994), 150-151.

[9] Booty, Mission, 170.

[10] Booty, Mission, 247-331.

[11] Board of Trustees Minutes, June 24, 1923, Board of Trustees of Virginia Theological Seminary, Alexandria, Virginia.

[12] Goodwin, History, Vol II, 553.

Mitzi Budde, D.Min, Head Librarian and the Arthur Carl Lichtenberger Chair for Theological Research, retires after 33 years. The Rev. A. Katherine Grieb, Ph.D., ’83, reflects on the profound impact she has had on VTS.

The Thomas Dix Bowers Preaching Fellowship Fund was established at Virginia Theological Seminary on May 6, 2008, by family and friends of the Rev. Dr. Thomas Dix Bowers, VTS ’56.

The Rev, Rode Molla, Ph.D., Assistant Professor, and the first Berryman Family Chair for Children’s Spirituality and Nurture at Virginia Theological Seminary, reflects on the legacy of the Rev. Jerome Berryman, D.Min.

Virginia Theological Seminary was honored to confer the Dean’s Cross for Servant Leadership on Ellen Wofford Hawkins in recognition of her deep faith and ability to bring sunshine into the lives of others.