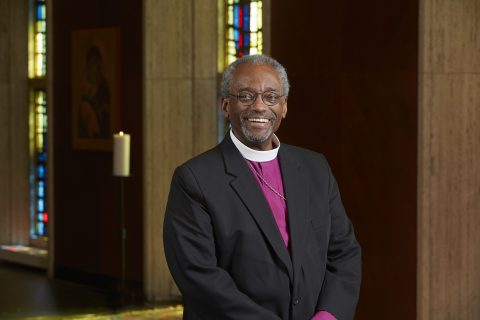

And thus, within mere weeks of passing the Presiding Bishop’s crozier to his then yet-to-be-named and elected successor, Bishop Curry warned of the dangers of a society morally adrift. He spoke, as in summation and near the end of his wide-ranging oral history that he has now donated to the archive of the African American Episcopal Historical Collection (AAEHC) at Virginia Theological Seminary (VTS). His warning is his powerful and unsettling prophetic voice for our troubled times – his prophetic voice that evolved over the course of an astonishing and accomplished life as an Episcopal priest, a black Episcopal priest, a diocesan Bishop, and the first African American to be elected to serve as the ecclesiastical leader of The Episcopal Church.

On June 12, 2024 I met with the Most Reverend Michael Curry to explore the spiritual and theological journey that has brought him to the close of his historic term as Presiding Bishop. Bishop Curry’s life is peppered with major “firsts.” Before Presiding Bishop, for example, in 2000 in the Duke Chapel in Durham, NC, he became the first African American in the American south to be consecrated as diocesan bishop.

It was my privilege and an honor to speak with Bishop Curry via Zoom, as he set out to bear Christian and prophetic witness during these momentous times in our national life. His oral history therefore takes its honored place in the AAEHC. As a repository of the history of Black Episcopalians, the collection could not be complete nor credible without his history. Prior to sitting for this interview, Bishop Curry agreed that the AAEHC would accession the zoom video and its transcription (its official record) to become fully accessible and held in perpetuity at VTS’ Bishop Payne Library in Alexandria, VA.

The AAEHC, a partnership of the Historical Society of the Episcopal Church and the Bishop Payne Library, collects and archives the history of black Episcopalians, and has been doing so for more than 20 years. Its collection contains recorded oral histories of many black Episcopalians, and it is the definitive repository for those stories. It was essential to accession Bishop Curry’s oral history.

Like most oral history subjects, Bishop Curry speaks fondly of his childhood living in Buffalo, NY, with his father and grandmother – his mother having died during his earliest years. His father was an Episcopal priest, and Curry recalls with loving and muted tones the diffused easy images of his boyhood in and about his father’s church.

He left home in the early 1970s to go east to New York’s Hobart and William Smith College. It was there that his thoughts about public service and social change began to take form as a call to ordained ministry. He began to seek guidance and wisdom in conversations with mentors, “sort of like Nicodemus going to Jesus at night,” he says. At the end of college, taking no hiatus, he went directly to seminary at Berkeley Divinity School at Yale.

At this point, he speaks with nostalgia about his seminary journey and its influence on what would become his preaching style – speaking with a rhythm and a pulse that fueled his early prophetic voice. After a field education assignment in a mostly black and West Indian congregation (St. Luke’s, where civil rights activist W. E. B. DuBois had been baptized), he was assigned to the predominately white (but racially mixed) St. Paul’s, in New Haven. St. Paul’s shared cultural and liturgical values similar to his childhood church of St. Philip’s, if not slightly more mainstream New England. It was there that he began to know and to see that there is little distinction among human beings of faith. He speaks here of the realization then that we are all, no matter what (referring to Howard Thurman), to be “in union or communion with the very source of our life itself.” We are all shaped by “that hand that is divine… Folks are on the same quest.” That combined field education and training gave him an ecumenical context in which to work, having been influenced earlier in life by black clergy “for whom preaching was the center of their lives.” He put that multi racial exposure to good use in Berkeley at Yale, that provided a foundation of rigorous training embedded in classic Protestant tradition.

Building on those earlier ecumenical years, the present-day Bishop Michael Curry brought to the larger mostly white Episcopal denomination the preaching style and witness of the Black Church. He said he had to. After Yale and following his ordination, he went to a predominately black parish in Lincoln Heights, OH, just north of Cincinnati. There his church community included some communicants who were semi-literate, whose forbears from the 1930s and earlier could not read or write. On Sunday mornings, he had to speak to the “semi-literate and the Ph.D.’s and M.D.’s who were children of that semi-literate generation,” all in the same room at the same time. There he learned to meet the challenge of finding an effective way to communicate – he had to preach, and in the style of and in the cadence, rhythm, context, of the Black worship tradition, such as calling on the Old Testament prophets – calling on Amos and Jeremiah. He describes this capacity to reach varied demographics together, at the same time and in the same place, as having to find his “personal Pentecost” that accompanies and effectively communicates a “muscular, prophetic, theology” of a variety of voices.

Bishop Curry movingly speaks of the need for that voice – especially in a gritty, urban place like Baltimore. There he served as Rector of St. James “where the seeds of injustice were so clear. [You] had to do hard preaching there…where the preaching must engage the life of the city… And if it doesn’t engage the life, it doesn’t live. And that is where whatever prophetic voice I have, or have had, had to come out. It was just forced… To speak the word in season.”

In closing he extends his tribute to his predecessor, Bishop Katherine Jefferts Schori, and her successful tenure as Presiding Bishop. She steered the church and held it aright during a most socially and theologically tense time in the Church’s history. At the close of her term in 2015, it was a good time to take up the Presiding Bishop’s crozier. What did he need to do? He needed to “help the Church reclaim, without embarrassment, our faith in Jesus Christ.” Of his tenure as Presiding Bishop, he says: “My calling was to ignite a revival that would feed the church for the days that are ahead of it, to feed the Christian movement for the days that are ahead of it… Time will tell, but I think that was my job.”

Yes, he led a Revival. And in all ways his own personal Pentecost was, and is, fully at work throughout the Church.

“I have been blessed,” he concludes. “I believe in God. This God is for real, and ministry for me has not been easy. Being Presiding Bishop has not been easy. Being a bishop has not been easy. You know, Langston Hughes, the poem From Mother to Son, ‘Life for me ain’t been no crystal stair,’ but I’m still climbing.”